Critical and feminist pedagogy for the development of spectatorial skills and receptivity in expanded theatricality

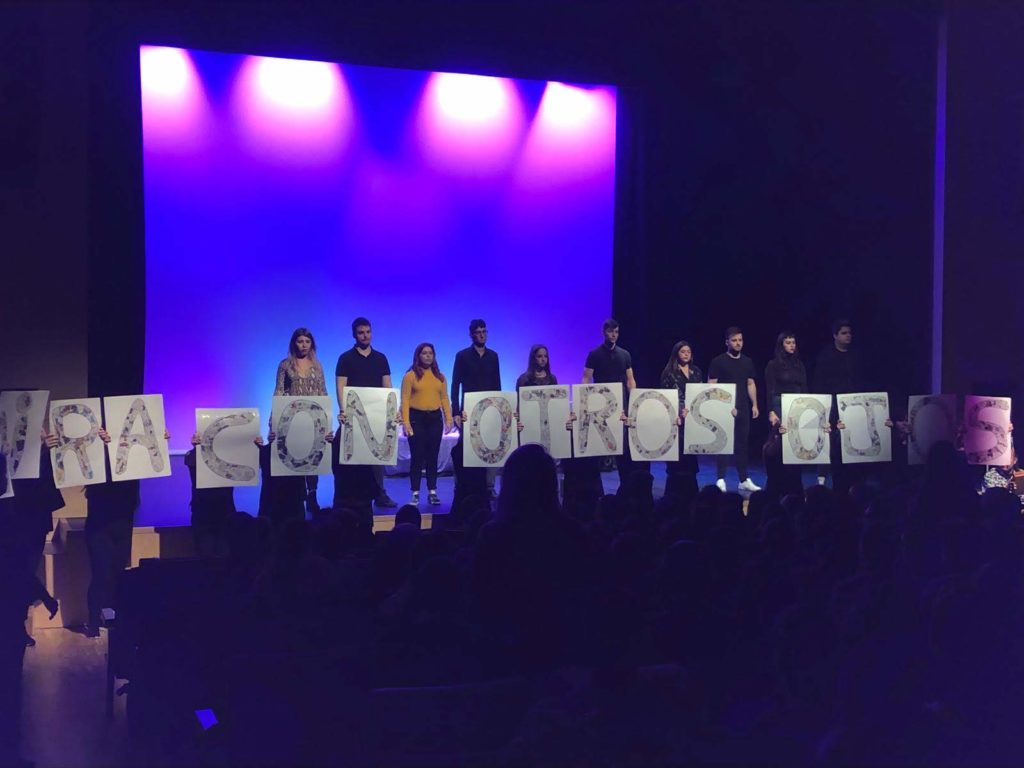

Once the performance had been staged by them, they carried out a group dynamisation, in Figure 1, where they also acted as mediators between the play and secondary school students (ESO) who attended as spectators. The objectives of this dynamic methodology were: to activate reflection and dialogue on the themes of the play; to facilitate understanding or teach some elements of the play that had not been understood; and to enable secondary school students to make proposals for possible solutions to the problem of gender violence presented in the theatrical performance.

Figure 1. Dynamisation grouping.

The dynamisation process that takes place after the presentation of the play consists of three stages: (a) Activation of dialogue and reflection through dialogic-reflexive critical pedagogies for affective involvement in the scenes performed (Villanueva, 2019); b) Facilitation of learning for the understanding of the play (Motos, Navarro, Ferrandis & Stronks, 2013) and the problematisation of tacit gender knowledge such as micro-chauvinism (Santos, 2020); and c) Creation of audience-generated narratives and development of the audience’s spectatorial competence with a feminist gender approach (Helbo, 2021; Boal, 2002).

These strategies fulfil the function of giving a re-reading of the theatrical performance from different perspectives and critical analysis by means of some strategies such as a) the comparison and exemplification of the thematic of the play with other facts of reality; b) questioning what is known, what is understood, what is felt; and c) valuing the experiences and interests lived by the spectators, in this case, the adolescents of the secondary schools.

At this point, the students’ first appreciations of what they have seen in the play emerge. In some cases, they feel identified with the topic; in others, they feel that the topic of micro-chauvinism is very distant because they have not experienced it; there are also some cases in which they comment that they know “someone” who has experienced it. These are free comments that arise spontaneously in the group context in which the mediator gets involved in a horizontal way to activate reflection and dialogue.

Mediator: Have you seen a scene or some of the sentences in which you have seen yourselves reflected?

ESO student (girls): What they said about fear when you go home, that’s all the time.

As we have said above, this strategy aims to facilitate the understanding of elements that have not been understood or that have not appeared explicitly. In this case, we see that the dialogue becomes less spontaneous and more guided by the mediators. Facilitation, in this context, is a space to generate transferential processes of contents linked to gender issues and the identification of similar situations or stories in the personal experiences that ESO students share with the group.

ESO student (boy): In general, there are many articles, for example, “this man was assaulted by his wife and everyone laughed at him”.

Mediator 2: Do you consider this to be male violence?

ESO student (boy): Male chauvinist if the woman hits the man, no, in this case it is from the woman towards the man.

Other strategies linked to the promotion of audience participation also emerge, not only through dialogue about their perceptions or life stories associated with the theme of the play, but also by contributing new ideas from a critical perspective. Here the approach is to rethink and imagine another possible reality that is more respectful and egalitarian. This is an action of recognition and trust in the knowledge of the spectator as creative and transformative subjects who “challenge”, “destabilise” the social constructions that are considered oppressive, in order to try to change them.

Mediator: If you notice when the boys say phrases, they are against micro-chauvinism. If you think of a situation, you have to transform that situation into a sentence that represents the opposite. For example, what happens if you don’t ask for the password of your mobile phone? Leave them alone, they can do whatever they want. Take a stand in this situation.

The idea of being a “transformative participatory spectator” is not easy for ESO students, since, as an “audience” they are not prepared to encounter a play in which they will be made to participate and get out of their “contemplative” role to get involved in an active role and change through their opinion. Participating in the subsequent theatrical “recreation” proposed by the mediators entails in the dynamisation groups organising and resolving who will be the “spectator-actor”, the “spectator-actress” who will manifest herself from the audience or from the stage space, in Figure 2. It is a moment of exposure that not everyone is willing to assume, so here the role of mediation is fundamental to persuade them and motivate their participation, not only with their reflections in the dialogue, but also by embodying the transforming reality.

Figure 2. Secondary school students acting on the transformative proposal.

Finally, the “contemplation” of the theatrical performance, the reflection and dialogue after its presentation invite the ESO audience to become part of a change in the reality presented in the play. This change is realised through their embodied participation, considering this concept as the action of “embodying” both verbal and “acted” contributions in the recreation of the play. In this sense, the “game” of embodiment has the immediate objective of favouring the capacity to “imagine”, within the metaphorical theatrical context, inviting secondary school students to be able to see other possible realities through the participatory commitment to change the previously “contemplated” reality.

What if I don’t want to wear a bra, what if I don’t want to be rescued by any Prince Charming, what if I am more than a sexual object?

“I as a man can’t tell a woman what to do if she doesn’t want to do it”?

“They don’t need your compliments”.

Thinking from this imaginative perspective, we see a pedagogical opportunity in the inclusion of the students with their bodies, their voices or their opinions about what they have seen in the theatrical performance. This is a moment of pause to observe the reality of gender violence that they possibly observe in their daily lives, but which, when they see it reflected in a series of narrative-visual passages, dialogue them as a group and embody them by becoming an integral part of this reality in order to transform it, offers other possibilities, other perspectives to think about a possible more respectful and egalitarian reality.

References

Boal, A. (2002). Games for Actors and non- actors. Routledge.

Helbo, A. (2021). La metamorfosis del espectador y la competencia espectacular. Tropelías. Revista de Teoría de la Literatura y Literatura Comparada, 35, 11-22. https://papiro.unizar.es/ojs/index.php/tropelias/article/view/5074.

Motos, T., Navarro, A., Ferrandis, D., y Stronks, D. (2013). Otros escenarios para el Teatro. Ciudad Real: Ñaque.

Santos, B. (2020). Teatro de las oprimidas. Estéticas feministas para poéticas políticas. Del Signo.

Villanueva Vargas, M. C. (2019). Opening spaces for Critical Pedagogy through Drama in Education in the Chilean classroom [Tesis de doctorado, Trinity College Dublin. School of Education]. Archivo digital. http://www.tara.tcd.ie/handle/2262/86151.

Author:

Yasna Patricia Pradena García

Citizenship, Ecologies of Learning and Expanded Education Research Group (CEAEX)

University of Valladolid