How and where do young university students learn? Conceptions, strategies, technologies, and contexts in their learning trajectories.

These conditions have meant that, in this generation, which is digital by birth, young people use multimodal forms of communication and information search, giving preference to non-textual content platforms. In the same vein, they have shown a preference for the role of observers, looking for real practical examples before applying their learning. They also express the need to understand such applicability in order to be involved in the process. On the other hand, many of them show an interest in social justice issues, have proven to be much more receptive to gender identity issues and, recently and increasingly, to environmental and climate change issues. But, as Livingstone (2017) points out, many interpretations of this generational data can lead to hasty conclusions, especially in relation to young people’s use of digital technologies.

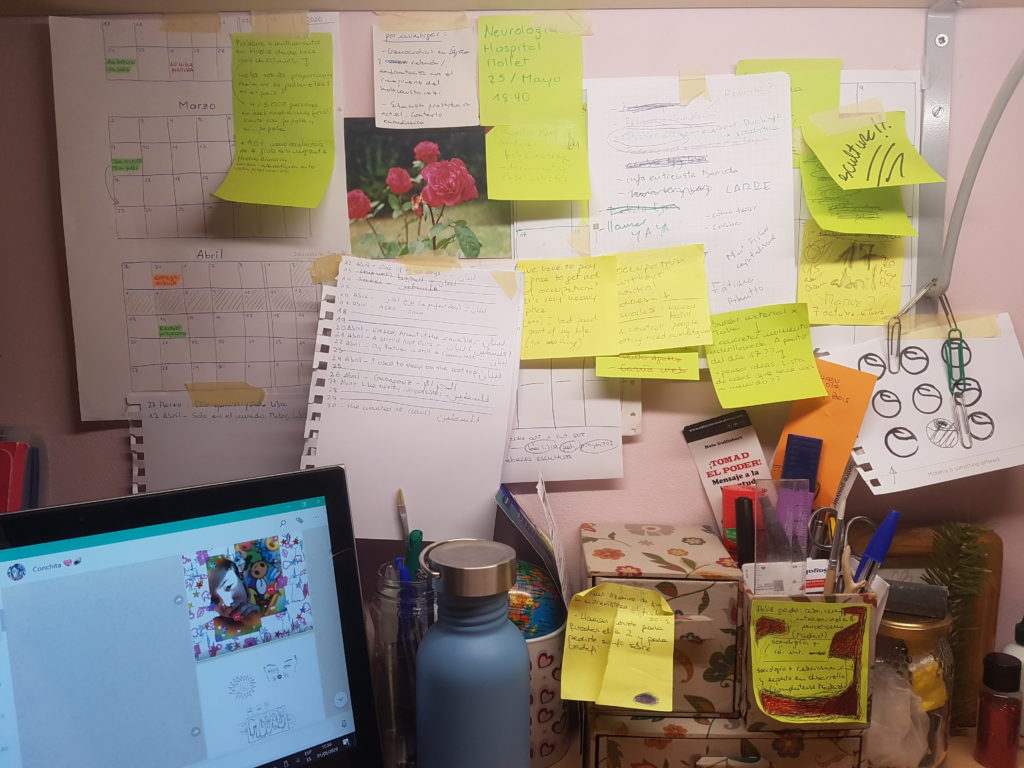

Picture of Clara Urquiza.

All this considering the possible problems of dispersion, superficiality and the addictions promoted by persuasive technologies. Therefore we set out to carry out research that would offer ways of understanding the questions: how do young people learn inside and outside the university, what are their conceptions, strategies and contexts, as well as the role of analogue and digital technologies, in their learning processes?

Answering these questions requires, as Erstad and Sefton-Green (2012) and Jornet and Erstad (2018) have argued, a research focus on individualised monitoring of young people’s learning trajectories. This invitation led us to propose the project “Trajectories of learning of young university students: conceptions, strategies, technologies and contexts (TRAY-AP)”.

This leads us to try to deepen and understand the changes that are taking place in young university students in relation to the meaning they give to learning and knowing, the strategies they use to move between studying and learning and the learning contexts (Jornet and Erstad, 2018) through which they move inside and outside the university.

To favor our modes of understanding, the TRAY-AP project has been planned and carried out from an inclusive onto-epistemological, methodological and ethical position (Nind, 2014) and based on a relational and performative ethics (Geerts and Carstens, 2019), Following these two axes implies considering the “Other” as a being in becoming who is a bearer of knowledge and experiences. The research is inscribed in a relationship in which the participants can show themselves as subjects in becoming in their relationships with learning and knowledge. The research involved four intensive conversation sessions with each of the 50 participants, in which various methods were used: dialogue with a text reflecting the research’s visions of the young people, drawing up a biogram or learning trajectory, a diary in which meaningful learning situations are recorded, and dialogue on the narrative that gives an account of the trajectory and ecologies of learning. These methods, which have served as triggers for reflection on their moments, contexts and learning experiences inside and outside educational institutions, have enabled them to contribute reflections and experiences in oral, textual or multimodal form.

The generosity of their reflections gave us access, among many other dimensions, to the meaning or meaninglessness of what the university offers them, their ways of dealing with learning and their ideas about how to promote a meaningful university education. The conversations were transcribed, arranged to facilitate their analysis in a table with two columns. In the right-hand column, the transcript is divided into extracts (they reflect the thematic unit) and these into fragments (questions are noted within the themes); and in the right-hand column we have placed specific ideas that emerge from the corresponding fragment, and which are related to the four axes of the study: conceptions, strategies, technologies, contexts related to the learning/learning of young people.

From this form of analysis, as a form of dialogue from concepts, derive contributions that call for pedagogies that are open to what real learning is, pedagogies that can be fed and nurtured by a pragmatics and ethics of the suddenly possible (the unexpected). Such pedagogies would then be pedagogies of the event, pedagogies against the state, disobedient pedagogies, in their sites of practice (Atkinson, 2018, paraphrased).

References

Atkinson, D. (2018). Art, disobedience, and ethics: The adventure of pedagogy. Springer/Palgrave Macmillan.

Broennimann, A. (2017). Generation Z Report. Swiss Education Group. Recuperado de https://www.thegeneration-z.com

Erstad, O., & Sefton-Green, J. (Eds.) (2012). Identity, Community, and Learning Lives in the Digital Age. Cambridge University Press.

Geerts, E., & Carstens, D. (2019). Ethico-onto-epistemology. Philosophy today, 63(4), 915-925. DOI: 10.5840/philtoday202019301

Haidt, J., y Lukianoff, G. (2019). La transformación de la mente moderna: Cómo las buenas intenciones y las malas ideas están condenando a una generación al fracaso. Deusto.

Jornet, A., & Erstad, O. (2018). From learning contexts to learning lives: Studying learning (dis)continuities from the perspective of the learners. Digital Education Review, 33, 1-25.

Livingstone, S. (2017). iGen: why today’s super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy – and completely unprepared for adulthood, Journal of Children and Media, 12(1), 118-123, doi: 10.1080/17482798.2017.1417091

McCrindle, M., y Wolfinger, E. (2009). ABC of XYZ : Understanding the Global Generations. UNSW Press.

Nind, M. (2014). What is Inclusive Research? Bloomsbury.

Seemiller, C., y Grace, M. (2016). Generation Z goes to college. Jossey Bass

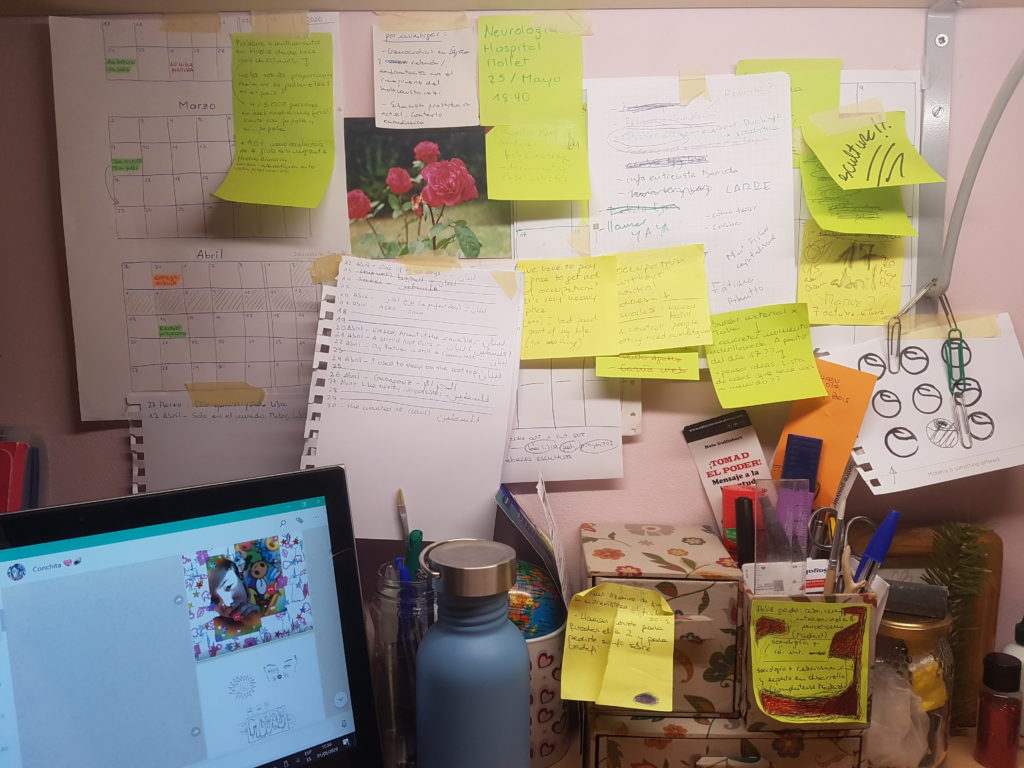

Picture of Clara Urquiza.

Authors

Fernando Hernández-Hernández, Professor at the Cultural Pedagogies Unit of the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Barcelona. Member of the Esbrina Research Group, https://esbrina.eu/es/inicio/ and the Indaga-t teaching innovation group, http://www.ub.edu/indagat/el-grup/.Member of the REUNI+D network.

José Miguel Correa Gorospe, Professor of the Department of Didactics and School Organization, Faculty of Education, Philosophy and Anthropology of San Sebastian University of the Basque Country/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea. Member of Elkarrikertuz (www.elkarrikertuz.es/inicio). Member of the REUNI+D network.

The project is funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, (PID2019-108696RB-I00), and is developed in the period 2020-2022. It is coordinated by Esbrina research group of the University of Barcelona and Elkarrikertuz research group of the University of the Basque Country.