The Inclusion Still Pending: Truly Feeling Part of It. Based on a research experience with deaf students with cochlear implants

Yet inclusion does not materialize through words alone. The deeper challenge—emerging from the most ordinary, the seemingly small—is to give substance and meaning to that promise: transforming the spaces we inhabit so that every person, with their particularities, not only has a place but can develop and participate fully.

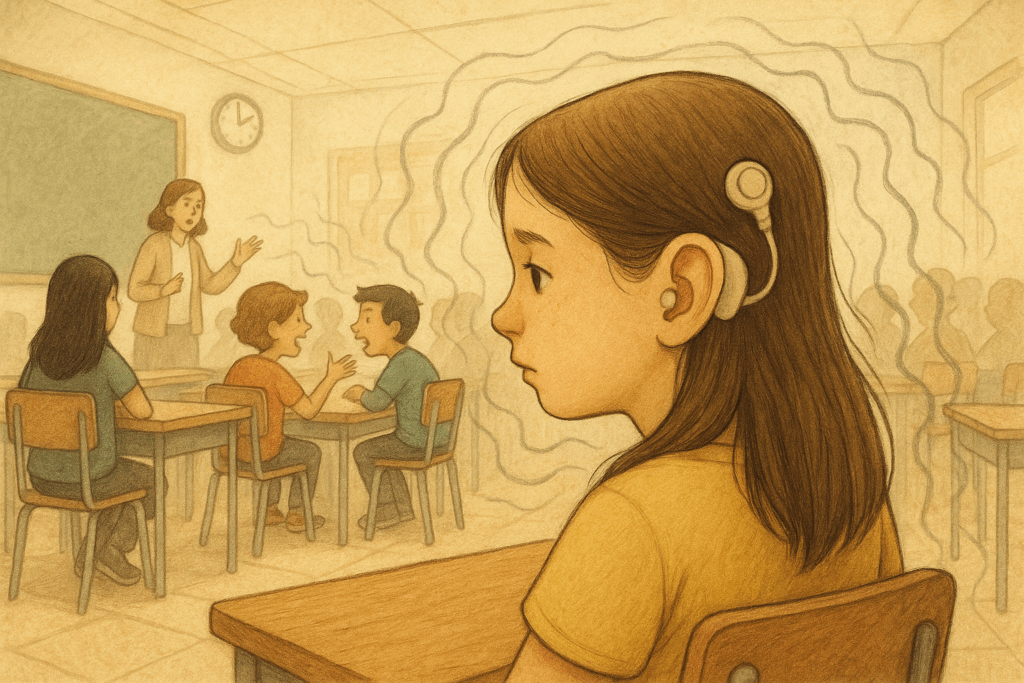

A clear example of this challenge is found among deaf students who use cochlear implants. Cochlear implants have been described as a medical revolution—and indeed they are, enabling many people with profound deafness to access sound and spoken language. However, mistaking this technological achievement for a definitive solution would be a misguided. The device itself does not resolve the pedagogical, communicative, and social dilemmas that arise in schools and other spaces of socialization. The inclusion of these students remains unfinished business—an open question for both the educational system and society as a whole.

The IC-EDUCA project (UMA Research Plan, code JA.B2-11) stems precisely from this uncomfortable question: How are deaf students with cochlear implants actually being supported in schools? The study seeks to identify the methodological, communicative, and organizational conditions that enable real inclusion—one centered on participation and holistic development.

Between Clinical Advances and Pedagogical

Research on cochlear implants has been abundant in the clinical arena, but scarce in the pedagogical one. We know how the device works, but much less about how these children actually experience everyday school life (Moreno-Torres & Fredes, 2012). Evidence shows uneven outcomes (Moruno, 2016): while some students reach levels similar to their hearing peers, others show delays in oral comprehension or reading. The causes are not solely medical; they also depend on the quality of educational experiences and communicative accessibility.

Still, our stance goes further: What lies behind academic success or failure? Can we talk about life success? Beyond grades and test scores, what happens in the emotional and social worlds of those who appear “normalized,” at least from the standpoint of academic performance?

Our ongoing research invites us to look more closely at the realities hidden behind Good or por grades. In some cases, we find students who excel academically but simultaneously face significant personal frustrations and limitations in their social relationships. Children with high marks, yes, but also with feelings of loneliness, struggles to fit in, or a persistent sense of not belonging.

The School as a Space of Inequality… or Opportunity

For years, the institutional response for deaf students was placement in special schools. Legal reforms promoted their enrollment in mainstream schools (Ruiz Vallejos, 2016), but full inclusion remains incomplete. Physical presence alone does not guarantee participation—or inclusion.

The barriers described above, invisible to those who do not experience them, sometimes turn school into a space that reproduces inequalities. However, acknowledging these barriers is the first step toward transforming them. Schools can become places where diversity is understood as an asset. Inclusion is not a concesión, it is a right that must be built collectively. It demands everyday activism, a constant commitment to equity, which in turn requires strategies that move us toward broader inclusive processes. Deaf people, like everyone else, have their own cultural, linguistic, and perceptual particularities.

Inclusion, understood as a process rather than a destination (Ainscow, Booth & Dyson, 2006), does not simply mean “being there.” It means participating, learning, and being recognized. It entails transforming school culture to value difference as a pedagogical opportunity, not a problem. An inspiring example is the series Romi (Azkoitia, 2025), which offers a fascinating take on hearing disability: Romina Goitia, “Romi,” is a private detective in her thirties whose deafness -having a cochlear implant in one ear- has given her an exceptional perception of the world. Her finely tuned attention to gestures, emotions, and tactile cues makes nonverbal communication her main investigative tool.

In this regard, the IC-EDUCA project shows that strategies initially designed for deaf students -such as improving classroom acoustics, using visual supports, promoting participation, or repeating key information- benefit the entire educational community. Inclusion does not take away; it adds. Talking about inclusion is not about making concessions to a minority—it is about improving educational quality as a whole.

Inclusion as politics, pedagogy, and attitude

True inclusion is not limited to resources or legal frameworks, it is an ethical and relational commitment. Every child perceives and inhabits the world differently; within that diversity lies educational richness. As Domínguez (2009) reminds us, inclusion is not a place but an attitude: choosing not to turn differences into obstacles but into opportunities to grow together.

Achieving inclusive education requires rethinking structures, methodologies, and mindsets. It means moving from “integration” -adapting to an existing system- to transformation, where the school reinvents itself in response to diversity. Inclusive education does not begin with major reforms or endless theoretical debates (Echeita, 2025). It begins with small everyday actions: how the classroom is organized, how we listen, how we acknowledge the Other. These details draw the line between merely being at school and truly feeling part of it.

References

Ainscow, Mel, Booth, Tony, & Dyson, Alan (2006). Improving schools, developing inclusion. London: Routledge

Azkoitia, I. (Director) (2025). Romi [Serie de televisión]. Joko TV. Disponible en Amazon Prime Video.

Cortés-González, Pablo (2024). Palabras para Julia. Márgenes, Revista de Educación de la Universidad de Málaga, 5(2), 196-202. http://dx.doi.org/10.24310/mar.5.2.2024.20170

Domínguez, Ana Belén (2009). Educación para la inclusión de alumnos sordos. Revista Latinoamericana de Educación Inclusiva 1 (3), 45-61.

Echeita, Gerardo (2025). La educación inclusiva en España. No está muerta, pero vamos hacia atrás. Revista Contrapuntos en Educación 1 (1), 51-67. https://doi.org/10.24310/cpe.1.1.2025.22107

Moreno-Torres, Ignacio y Fredes, Eliana (2012). El desarrollo lingüístico en el niño sordo implantado antes de los 24 meses: Un proceso similar al del oyente, pero con tiempos diferentes. Separata de la Revista FIAPAS. https://bibliotecafiapas.es/pdf/Revista_FIAPAS_157.pdf

Moruno López, Esther (2016). Desarrollo del lenguaje en niños sordos con implante coclear: diseño de un corpus y su aplicación al estudio de la fonología (Tesis doctoral, Universidad de Málaga). Servicio de Publicaciones y Divulgación Científica. https://hdl.handle.net/10630/13130

Ruiz Vallejos, Noelia (2016). El niño sordo en el aula ordinaria. Revista Internacional de Apoyo a la Inclusión, Logopedia, Sociedad y Multiculturalidad, 2(1), 19-32. https://revistaselectronicas.ujaen.es/index.php/riai/article/view/4191

Authorship:

Pablo Cortés González

HUM619 Research Group, ProCIE.

IFE.UMA Research Institute

Universidad de Málaga