Thinking about educational research from the collective construction of meaning: a travel log

We began the seminar by exploring, from an individual reflection, the benefits and barriers of collaborative networks in education. Then we exchanged these reflections successively in pairs, groups of four, groups of eight, until we reached a large group discussion. In this way, we identified commonalities from our individual perspectives.

Photograph showing the result of the dynamic on benefits and barriers of collaborative networks.

QR code. Link to the transcript of the information provided in the exercise.

Among the benefits are the opportunity to establish more horizontal relationships that allow for a broader perspective based on the diversity of knowledge. Projects that promote social creativity and offer opportunities to transform reality are linked to them. Among the barriers, we point out both individual and institutional resistance to building on dissent that which is common, showing a reluctance to open dialogue and negotiation of differences. Added to this is the difficulty of sustaining horizontal dynamics, where confusion between the individual and collective dimensions can lead to a lack of responsibility and commitment.

Then, we divided into four groups to think about the previous ideas we had in relation to collaborative networks linked to our research questions. During the activity, we rotated around the room where we had placed each of the questions on the wall and posted words that identified and represented these ideas. During the rotation, each group looked at what the previous group had written and completed it, thus creating a cartography for each of the questions presented below.

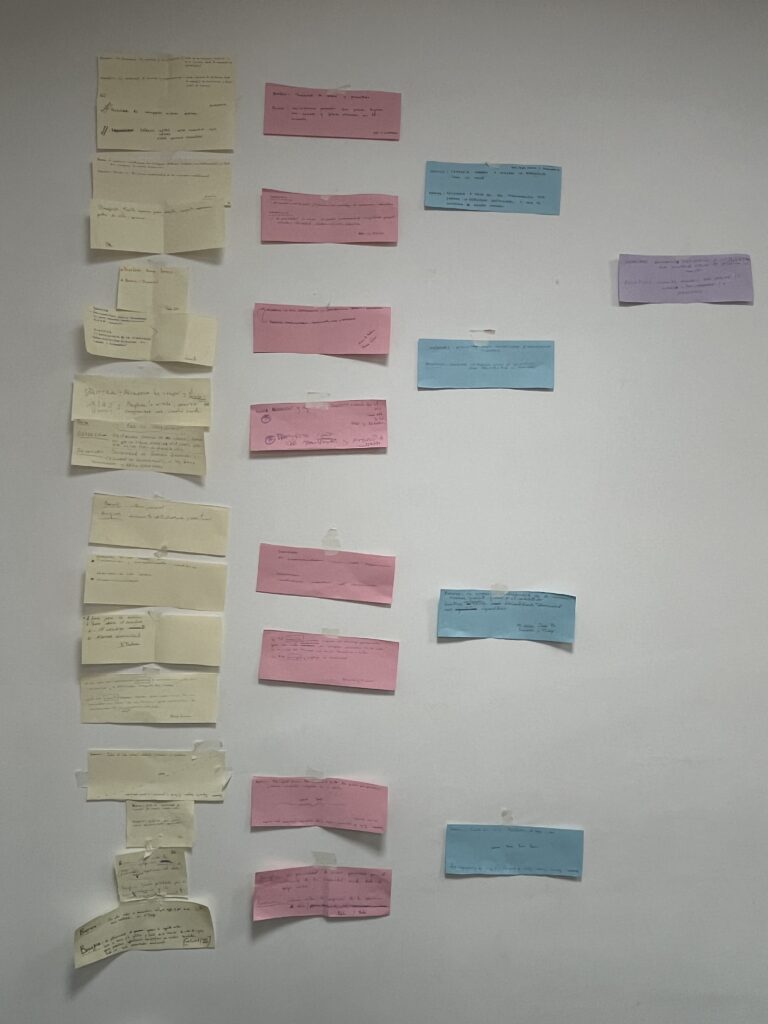

1. Why does a collaborative network in education emerge?

Collaborative networks in education arise as a response to professional loneliness and the limitations imposed by a capitalist context in crisis. They are shaped by the need for social connection and the desire to overcome exhausted pedagogical models through the curiosity to learn and research as a tool to explore new alternatives. In addition, factors such as scarcity of resources, systemic oppression and an attitude of rebellion drive their creation. Participants link this oppression with the need to build community, promoting values such as mutual help, visibility of their work and connection between peers.

Cartography research question 1.

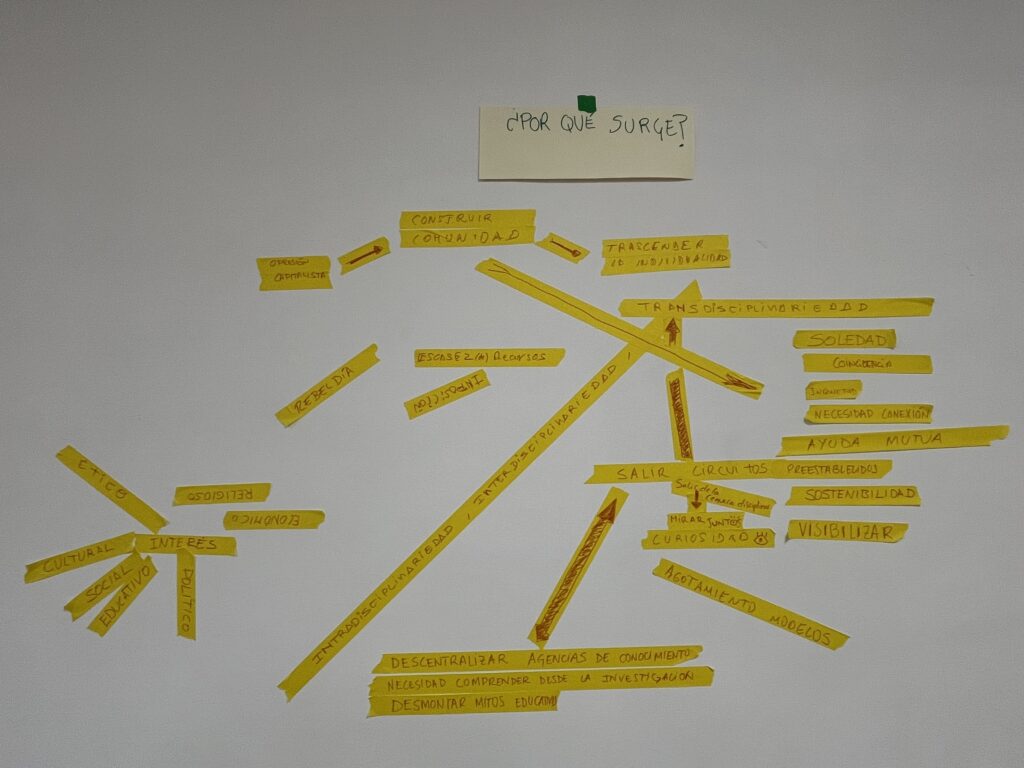

2. What is a collaborative network in education for?

These networks aim to rebuild damaged community links, promoting sustainability through mutual support, collective learning and transformative action. Their function transcends simple cooperation, seeking to generate positive change and address specific needs within specific social contexts. Some of their aims are: a) to build community and overcome individuality through actions that promote understanding of the world and joint learning; b) to foster research processes based on the analysis of collective experience, going beyond the limits of disciplinary theory; c) to promote social creativity through the dialogue of diverse knowledge to find innovative solutions to the challenges of the current context; d) to identify needs and lead improvement processes.

In short, these networks constitute spaces of emancipation that make it possible to imagine scenarios worth living in, placing transformative agency as a fundamental pillar of critical pedagogy.

Cartography research question 2.

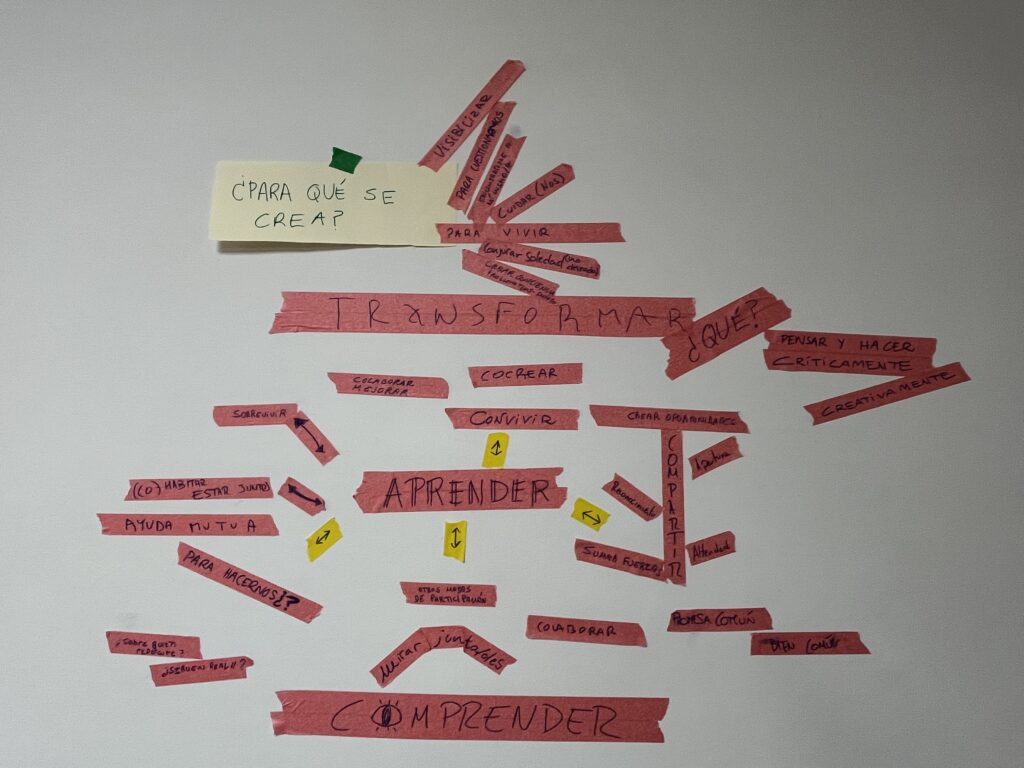

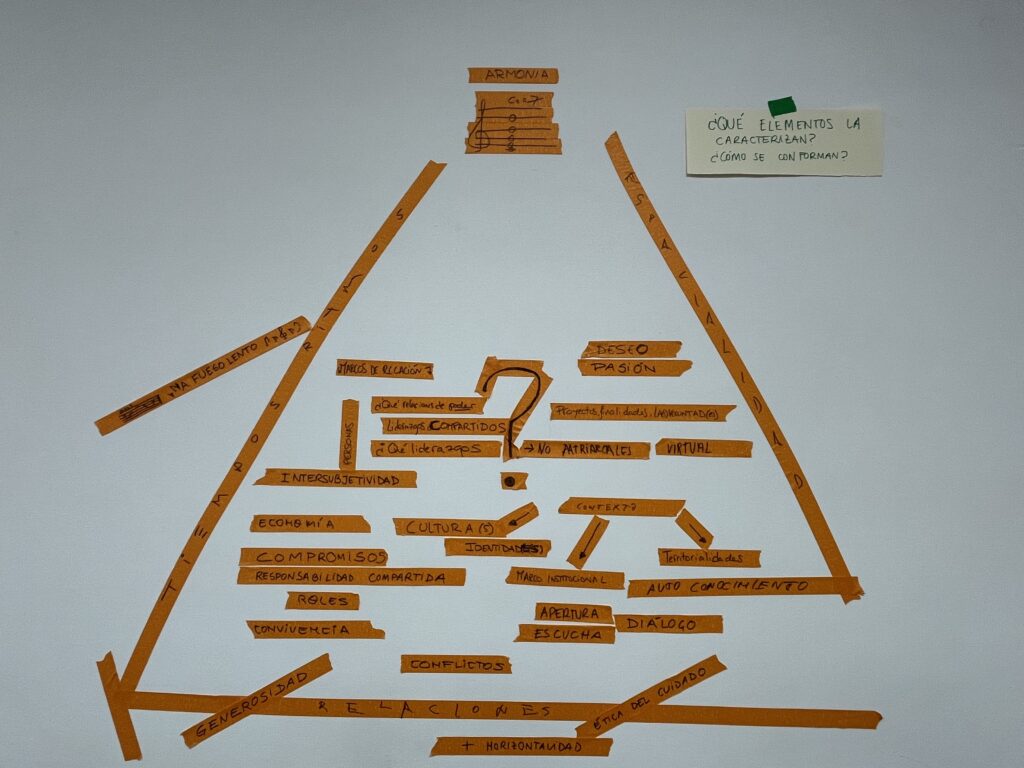

3. What elements characterize them and determine how they work?

This cartography identifies three essential aspects that characterize collaborative networks, and which are related to context, time and interpersonal relationships.

The institutional context and individual territorialities are factors that can facilitate or hinder the creation and development of the network.

Networks require alternative times to those imposed by capitalist logics of productivity, adapting to normative and personal rhythms to balance the individual and the collective.

The inter-subjective dynamics are based on: a) social, political and pedagogical commitment to take on shared tasks; b) dialogue to build consensus and resolve conflicts; c) distributed leadership that fosters equality and democratic participation; d) the ethic of care, focused on collective well-being; e) self-knowledge, the basis for authentic listening.

Cartography research question 3.

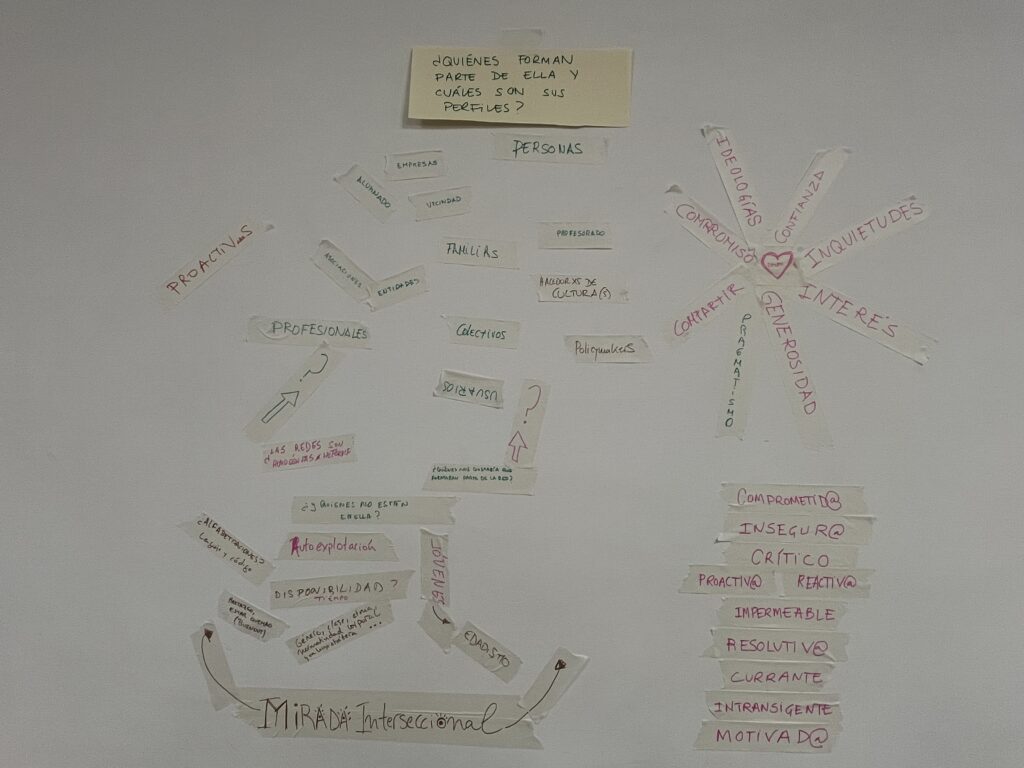

4. Who is part of them and what are their profiles?

Analyzing the profiles that make up collaborative networks is key to understanding how they work. However, it is equally important to reflect on who is absent, to identify barriers to access and to address factors of exclusion. These networks should include a wide diversity of actors – students, teachers, families, associations, cultural and business representatives – to enrich their dynamics.

Participants’ characteristics include a real desire to be part of the network, linked to values such as commitment, trust, generosity, pragmatism and the ability to share, together with skills such as proactivity, constructive criticism and motivation. However, tensions also arise due to ideological and policy differences, underlining the need to analyze how these differences are managed to ensure the smooth functioning of the network.

Cartography research question 4.

At the end of the meeting, an ontological, epistemological, methodological and ethical debate on educational research and its relationship with society was generated. This dialogue around the central concepts of our research resulted in a map of meanings that will serve as a guide throughout the process.

Word cloud from the question: what are the concepts articulated in our research?

One of the issues that came to the fore was the responsibility of the researcher in relation to the aims and approaches that are reflected in the reports and that are mediated by the prior ideas with which we approach the object of study. In this seminar, the dialogical, reflexive and even bodily movement – due to the rotation in space – around our research questions allowed us to identify these prior ideas to establish a common framework of interpretation and to become aware of the elements that are not there and to which we must pay attention when they arise in the development of the study.

As a research team, we consider it essential to continually reflect on and question the social, political, personal and institutional implications of the processes that are developed in and from the research. This seminar became a space that facilitated this awareness through collective reflection.

Authors:

Almudena Ocaña-Fernández

Research Group ICUFOP (University of Granada)

Analía E. Leite-Méndez

Research Group PROCIE (University of Málaga)