Expressive sovereignty for thinking about the meaning of school and teacher education

This initial position and the reflection over the last few years have shown us the need to take other expressive paths that break with the ones we usually use and share, which are generally of a literary and academic nature. In this way, we believe, we are opening up possibilities for making visible other meanings, other senses and other nuances of the school experience, as a sediment of teacher education in the university environment. In this sense, we understand expressive sovereignty as a way of breaking down the hegemonic discourses on education, training, learning and the autonomy of students, teachers and families. In this way we can advance in the construction of other school narratives and, therefore, of an education “other” as a possibility of transformation.

We understand, from a narrative and socio-constructivist epistemology, that stories construct realities, as well as the ways of telling and expressing them. Different expressive formats, therefore, open the door to thinking about and building another school and another education from other dimensions: the body, the heart, everyday life, affections, feelings, desires, etc., which are often hidden in the hegemonic standardisation in force in the academy. A text, an image, a drawing, a performance, a dramatization, a comic, a song, a poem, reveal other dimensions of people that are difficult to fit into the dominant written text. In this sense, we also recognise the inclusive sense of opening up forms of expression, as it generates a diverse, multiple and valid space that everyone can feel as their own. Literacy, in the current educational context, can represent forms of power and authority that relegate other knowledge and the subjects and collectives that carry it.

With these principles in mind, we present in this paper some experiences of stories with different formats that give an account of the meaning of school and the experiences lived in it, through other expressive formats that connect in a different way with the different subjectivities involved and reveal other meanings. Other structures/dis-structures predominate: superposition, combination, colour, collective, globality, rupture and disruption. It is very interesting to think about expressive sovereignty as a possibility that “anything goes” is possible, is viable and is also a discourse that is close to the real lives of children, young people and citizens in general.

A first experience is the result of an investigation with nine- and ten- year-old children who were asked to tell us what school has been like during the pandemic, what has happened to relationships, to spaces, to their own lives. In this sense, scenes of isolation, loneliness, new objects and symbols are recovered, but it is also possible to think about that school that they long for, that they wish, and to which they want to return, even if it does not return in the same way. In this research, we have used drawings as an instrument capable of bringing out thoughts and feelings that are difficult to express in words. A pretext – such as drawings – is a stimulus that can be used to motivate, stage and construct emotion (O’Neill, 1995).

A second experience takes place with university students, where teaching and learning processes are still linked to orality and literacy, almost exclusively, with references only to academic texts, such as articles or books. Academic tasks, such as monographs or essays, continues to be the bastion of teacher education while multisensory languages are part of the cultural and communicative dynamics of a large part of the population and of young people in particular. In this sense and based on the work with autobiographical accounts of the school experience, two pathways of analysis and interpretation are proposed. The pathway of the cartographies and the pathway of the performances. Although these formats are based on individual accounts, they seek collective expressiveness. The students bring into play their representations, their imaginaries, the references that have been shaped in their history, to express them in a graphic format that combines meanings, resources, languages and, most importantly, there are no academic or academicist filters involved. Free expression is freedom of action and imagination that provokes the group itself in terms of decisions and generates different expectations in relation to their productions and their formats and channels. This also provokes other forms of commitment, both personal and collective.

The path of the different performances, understood in a sense very close to that of the “theatre of the oppressed” (Boal, 2009), again provokes freedom but also tension in terms of putting bodies, hearts, cognitions, and actions into play. The grouping, in this case, is broader, with several groups working on the same dramatization. In this approach, they agree among the various participants in the performance what elements will be shown, what symbolism will be brought into play, for example, with the costumes, the props that will accompany them, etc. Often, they represent particular scenes from their stories; in other cases they manage to articulate a shared story that represents the collective perspective of their school experience; in other ones they create a meta-story, in which they include idealisations of different kinds.

Both the cartographies, or visual representations of the first nuclei of interest within the inquiry process, as well as the narrative performances, are two fundamental moments in the process of constructing knowledge of a subject, but fundamentally they are proof of their epistemological sovereignty insofar as the ways of knowing are embedded in the very ways in which the subjects decide to do so, from the group and for the groups.

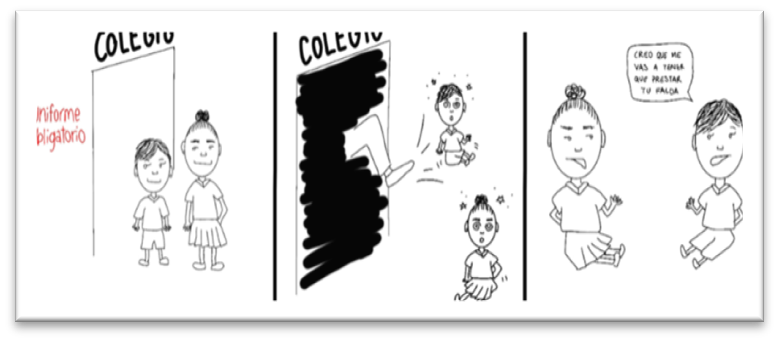

Along the same lines, another experience rescues the collective stories through comics, where the conditions in which they have been produced (they are collective productions), the contexts that have been brought into play and the collaborative elaboration that has made of all this set of data a story with a multiple language are present. This means giving value to the participants as producers of meaning and makers of processes with collective meaning. The importance of comics in training has shown us how they promote shared dialogue through creativity in action, as well as bringing into play other languages, times, symbols, and the creation of characters with styles and stereotypes that then challenge the group and the creators themselves.

In short, the different proposals presented remind us of the importance of accommodating different forms of expression as one of the key elements for the social and cultural participation of citizens. Our lines of research, open to different types of knowledge and ways of expressing it (in the form of artistic expression such as drawing, comics, collage, video and/or photography, among others), are shown to be a fundamental tool in initial teacher training.

References

Boal, A. (2009). Teatro del Oprimido. Alba Editorial.

O´Neill, C. (1995). Drama worlds: A framework for process drama. Heinemann.

Rivas, J.I., (Coord.) (2023). Soberanía Expresiva en la construcción del conocimiento educativo. VIII Simpósio DEDiCA EDUCAÇÃO E HUMANIDADESTM e/y XVII SIEMAI – Simpósio Internacional Educação Música Artes InterculturaisTM , celebrado en Escola Superior de Educação, Politécnico de Coimbra (Portugal)/Facultad de Educación, Economía y Tecnología de Ceuta de la Universidad de Granada (España), del 25 al 27 de enero de 2023.

Authors

Analía E. Leite Méndez

J.Ignacio Rivas Flores

Gustavo González Calvo

Grupo de Investigación PROCIE: Profesorado, Comunicación e Investigación Educativa.

Universidad de Málaga y Universidad de Valladolid.