Assistive Technologies in teaching as an inclusive challenge

We are witnessing the meeting between two extraordinary educational galaxies:Inclusion and Educational Technology. When galaxies cross paths and given their gigantic enormity, they do not collide, as they come into gravitational contact and rotate in a stellar dance of spirals where contact between their masses is very rare: they fuse without breaking anything, generating a new even bigger galaxy.

This is happening between the fields of Inclusion and Technology, a fusion of complicit views that in the last 30 years of educational postmodernism have advanced separately following their own challenges and their own milestones, attracted by “improvement” as a paradigm, are in the same gravitational field (Castillo-Olivares, 2023).

- Educational Inclusion advances from the universal right to quality education for all, and continues to generate colossal efforts (institutional, international, transnational, practical, political and cultural), which make possible equity closer every day.

- Likewise, Educational Technology advances from new applications and experiences that test new models to improve teaching. The creativity, adaptability, speed and versatility of digital universes allow us to explore the world of expanded realities, social networks, virtual environments and new intelligent realities, from a technological development that already allows attraction and demand for better technologies. assistance.

Among the assistive technologies defined as priorities by the WHO we will find translators, image magnifiers, alarms, light indicators, supports, communication amplifiers, language aids, sound decoders in touch pulses or sound transformers in letters.

In the last two years we have had the opportunity to investigate, together with a dozen European institutions participating in the Inclusion-Team project, about the state of development of technologies applied to Special educational needs. Its moment could be said to be that of its definition as a challenge inclusive, since contradictions emerge, pedagogical inquiry is demanded, and improved designs for new visible needs and studies of good practices are demanded (VVAA, 2023). For example, a lot of the main institutional websites and specialized research centers on special educational needs and assistive technologies that don’t have their own means of communication and dissemination developed under adaptive or supportive designs, they don’t have a universal design, they don´t have audio versions or tactile outputs, no organized information neither clarified meta for friendly navigability, or they simply don’t have a translation (UNESCO 2006, 2011, 2014).

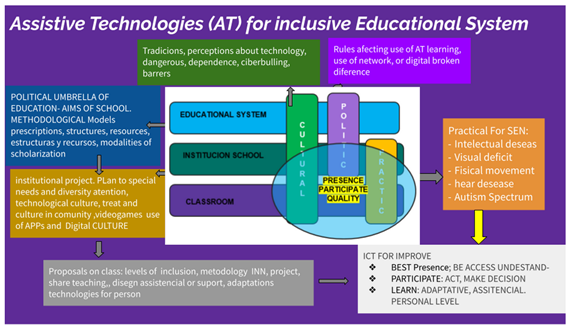

Decision-making ideogram according to levels of concreteness and inclusive dimensions for Assistive Technologies. Castillo-Olivares 2023

Nor do schools have universal accessibility, neither physical (they often still have no ramps), nor informational (media without adapters, translators, mediators or supports). Classrooms are filled with digital screens of different formats that are insufficient for viewing at 10 meters, or they are the new universal whiteboard (used as simple projectors). National technological support institutions are “exotic projects” of great political value, but little practical impact.

In the new generation of European educational policies, the language of competence focuses on a deep digital citizenship where, from our mobile phones, we check the traffic, the weather, we pay, we check our sugar, or we check the day’s caloric expenditure…

In this new reality, technologies have become essential and their universality requires their inclusive management with its three principles of accessibility, participation and quality. We believe that in the coming years this new educational constellation will continue to create great questions and great challenges, to which we must respond through research and innovation.

References:

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2023). European Agency Statistics on Inclusive Education: 2019/2020 School Year Dataset Cross-Country Report. (P. Dráľ, A. Lénárt and A. Lecheval, eds.). Odense, Denmark.https://www.european-agency.org/activities/data/cross-country-reports

European Commission (2019). Model for a ‘highly equipped and connected classroom’. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/information_society/newsroom/image/document/2019-10/ictineducation_objective_2_report_final_4688F777-CDED-C240-613EE517B793385C_57736.pdf

Castillo-Olivares, J.M. (2023).ICT applied to Inclusive Education: current events and good practices. Ed. Aula Magna Mc Graw Hill.

UNESCO (2006). ICTs In Education for People with Special Needs. Institute for Information Technologies in Education. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ULW-9c8vezc-V0MgDsgNDXeHWjx38aSv/view

UNESCO (2011). ICTs in Education for People with Disabilities. European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ul5TLNIl3EZlYtHXe3rr_CVfrvButHR8/view

UNESCO (2014) Model Policy for Inclusive ICTs in Education for Persons with Disabilities. UNESCO Communication and Information Sector, Paris. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1VLGl20vExhzn8U3WfHKZ–eH4xAJCDjT/view

VVAA (2023).Toolkit Apps integration in Special Needs Education. Inclusion Team European Project. Availablehttps://www.icteam.site/intelectual-outputs/pedagogical-toolkit

World Health Organization (2016). List of Priority Technical Aid.https://www.who.int/es/publications/i/item/priority-assistive-products-list

Authors:

José Mª del Castillo-Olivares

Desiré González Martín

Carlos José González Ruiz

Grupo de Investigación Laboratorio de Educación y Nuevas Tecnología

Universidad de la Laguna