Cartographies to Recognising Ourselves in Othernes

Cartographic practices, such as that described by Erica González (2013), allow us to analyse and rethink the leading academic, political and educational discourses installed in the school to build collectively. In this sense, we find different examples of working with cartographies in research. However, we are interested in those that allow us to encounter the other to unveil the discursive grammar of the school and to reveal the educational policy resulting from practices that have constituted the school’s identity for years and have been naturalised as standard in a shared way. We believe that artistic proposals allow us to approach complex issues using evocative and metaphorical language, such as otherness. The concept of cartography, which comes from the geographical field, has been transferred to educational research as a device for analysing and creating reality. This reality can be freely constructed rather than pre-defined and established. It allows us to break with the logic of positivist research and to accept that, as researchers, we interfere in mapping subjects, which must be considered part of the research process. Furthermore, this methodology allows us to unfold research, leaving the purely representational frame to understand as a process to open up new avenues. Thus, research focuses on the inseparability between subject and object, as well as between theory and practice. That implies recognising that research is not aseptic and involves multiple subjectivities that affect and relate to each other (Almeida & Bedin da Costa, 2021).

We are interested in the idea that maps represent the social structure of a place. Each map is conditioned by the production environment, just as its interpretation or the theory to which it may give rise is a reflection of the thinking of the time (Ball & Petsimeris, 2010). We can transfer this idea to the field of education and thereby seek to observe and make sense of what happens in schools. Constructing new stories and narratives requires tools promoting participation and encouraging reflection based on dialogical perspectives. As the collective Iconoclasistas (2013) stated, “The use of these resources broadens participatory research methodologies, and from the incorporation of creative and visual resources emerge expanded ways of understanding, reflecting and signalling various aspects of everyday, historical, subjective and collective reality” (p. 14). We can produce different artistic cartographic maps and observe how we cross these maps with learning theories and shared meanings among researchers to make sense of learning at school.

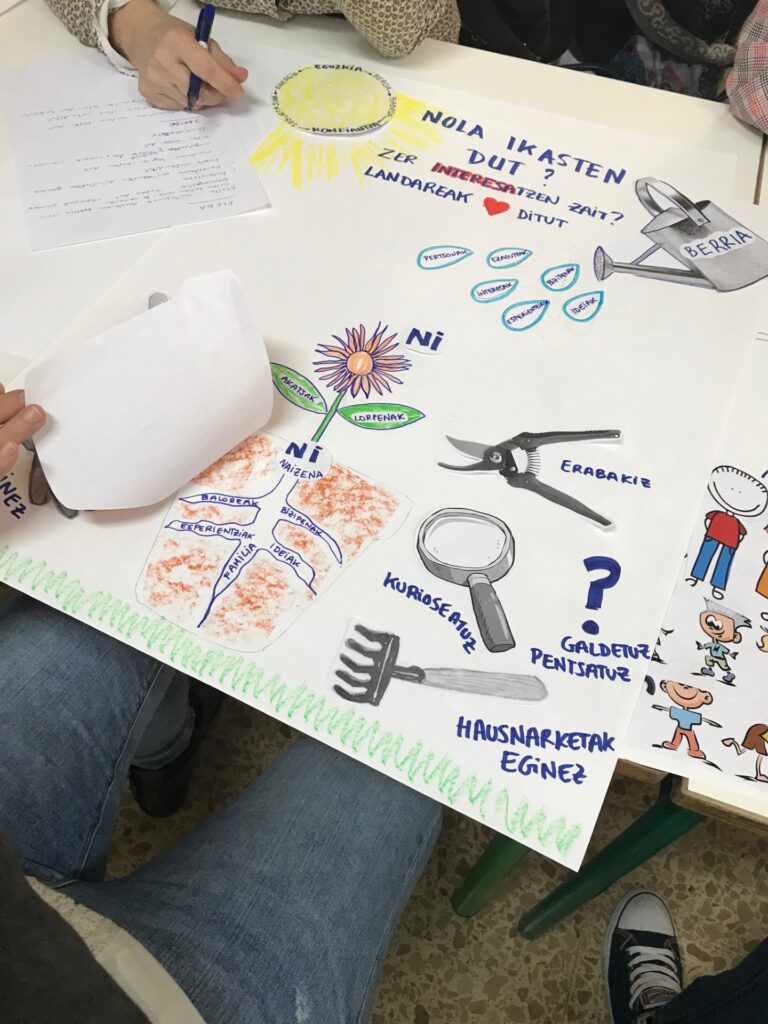

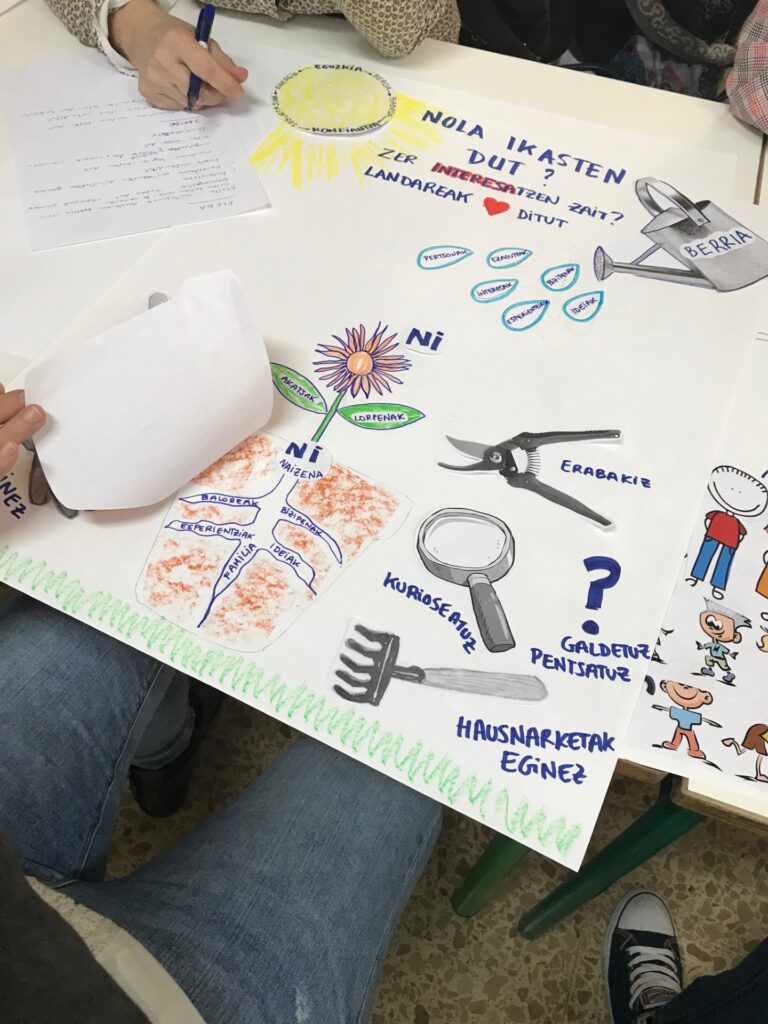

The framework or context of the action we will analyse occurred in a public school in a municipality in the Basque Autonomous Community (Spain) comprising an ex-industrialised territory on the banks of the Bilbao estuary characterised by degradation but undergoing regeneration. The school was committed to textbook-based teaching but was working on a process of change and improvement. The commitment of the school management team was to move to project-based teaching. In this framework, the school director proposed to launch a formation programme in which the school’s teachers would become agents of change. To this end, an artistic mapping workshop was proposed based on the question, “How do we learn?” The entire teaching staff of the centre took part in the action, 19 early childhood teachers and 34 primary school teachers. For this text, we will only focus on the visual analysis of this teacher education proposal, reviewing the scenes that account for otherness to reflect on the scope and possibilities of the cartographic experience and practice.

The framework or context of the action we will analyse occurred in a public school in a municipality in the Basque Autonomous Community (Spain) comprising an ex-industrialised territory on the banks of the Bilbao estuary characterised by degradation but undergoing regeneration. The school was committed to textbook-based teaching but was working on a process of change and improvement. The commitment of the school management team was to move to project-based teaching. In this framework, the school director proposed to launch a formation programme in which the school’s teachers would become agents of change. To this end, an artistic mapping workshop was proposed based on the question, “How do we learn?” The entire teaching staff of the centre took part in the action, 19 early childhood teachers and 34 primary school teachers. For this text, we will only focus on the visual analysis of this teacher education proposal, reviewing the scenes that account for otherness to reflect on the scope and possibilities of the cartographic experience and practice. Three necessary steps were fundamental to establish trust with us as accompaniers and with their colleagues, as those necessary to build a joint project. The actions were all recorded, and polysemic data were generated, with ambiguity and multiple meanings. In this chapter, we collaboratively approached these data so that the choice of narrative vignettes would give a dialogical account of the process experienced. We opted for an interpretative methodology based on reflective vignettes. To analyse the experience and subsequent discussion, we leaned on the strategy proposed by Michael Humphreys (2005), where a narrative based on the vignettes is established from the field notes, which, we think, is appropriate for the study.

The research to which this chapter is linked was focused on how teachers learn. In a related paper, we stated that “teachers learn in a web of relationships in which they link the biographical and the corporeal, as well as the cognitive (…) In particular, in relationships with colleagues and students” (Hernández et al., 2020, p. 22). We work with cartographies as a visual thinking strategy to explore the themes regarding learning and the teaching experiences linked to them and represent mental and emotional maps. For this chapter, we have focused on the notion of sharing as described by Carrasco-Segovia (2021): “Cartographies are not made to us, but to put them in relation with others” (p. 90). In working with cartographies, one objective is to place all school staff in the context of cooperation with others. Mapping aims to investigate the notion of learning and to draw a diagram of pedagogical actions following the emerging ways of learning. Therefore, mapping in addition to depicting relationships and meanings between ways of learning, allows us to establish listening relationships and a collaborative work process that opens up other pedagogical relationships.

The research revealed that a relationship is necessary to learn and, in this learning process, where all people have a place, we need to recognise ourselves in others. As the Catalan philosopher Garcés (2020) stated, “education is not an action on an object (the student, the learner, the creature…), but a relationship that is above all receptive” (p. 23). We seek to establish cooperative and reciprocal relationships with our research participants, and we believe that artistic methodologies offer a relational setting that allows for this. All this considering that, as Mannay (2015) reminds us, these collaborative creative practices need time. So, it is advisable to have a wide variety of options for fostering oral or narrative alternatives. Therefore, we call for a hybrid scenario in which knowledge derived from the arts is legitimised, knowledge is not reduced to data and openness to other epistemologies is allowed. If we want to recognise ourselves in the other, the notion of knowledge has to be renegotiated and shared, a knowledge that derives from the relationship with the other person. If we do not consider the other, we may accentuate differences and impose on them what we are without the option of discernment. Power relations are also present in creative practices, and it is essential to be attentive to the tensions that can arise. Tsalach (2013) stated that “the cumulative effect of these knowledge devices results in the construction of an imaginary world in which the ‘other’ is reinvented. This is done by imposing types of knowledge that reinforce colonial difference” (p. 469).

From experiences shown in the vignettes, we can see that when we transfer an artistic research methodology to an educational process, concepts arise as emerging problems that need to be addressed for a structural change in the school. We are aware that change is complicated without a relationship between the plurality of subjects where these concepts are problematised and where all teachers are recognised. Drifts that allow these tensions to emerge make them visible and can be worked on. In this sense, we consider that teacher education proposals based on artistic processes can decentre the meaning of the word to find a place where other drifts are produced, “it opens a space of horizontality in which everyone can find their place to say something else” (Riera-Retamero et al., 2021, p.190). In conclusion, when transferred to teachers’ professional development, we suggest that arts-based research approaches allow us to consider participants not as isolated entities but in permanent relationships with others. As subjects involved in all parts of the process whose prior knowledge and experiences are considered. Only by understanding that the people involved in this educational process are plural and considering their differences can we work in a relationship in which all participation is achieved without leaving anyone aside. Seeking a different relationship between educators and teachers requires a relationship of trust in which the other can be included. We must mitigate resistance and, within these processes, try to avoid denial or absorption of difference.

References

Aberasturi-Apraiz, E., Correa-Gorospe, J.M. (2023). Cartographies to Recognising Ourselves in Othernes. In: Carrasco Segovia, S.V., Hernández Hernández, F., Sancho-Gil, J.M. (eds) Affective Cartographies. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-42163-1_14

Almeida, T. y Bedin da Costa, L. (2021). Cartografa infantil: enfoques metodológicos seguidos de experiências com crianças e jovens de Portugal e Brasil. Infancia y Filosofía, 17, 01–24.

Ball, S. y Petsimeris, P. (2010). Mapping urban social divisions. FQS, Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(2), 1–20.

Carrasco-Segovia, S. (2021). Cartography: An artistic method to promote an affective and meaningfully learning. In Onsès-Segarra & Hernández-Hernández, F. (Eds.). (2022). Education and society: Expectations, prescriptions, reconciliations (pp. 86–93). Proceedings of ECER 2021.NW 29. Research on Arts Education. Geneva (online), 6–10 September, 2021, University of Girona – Dipòsit Digital, Girona.

Garcés, M. (2020). Escuela de aprendices. Galaxia Gutenberg.

González, E. (2013). Cartografías de la educación intercultural en México.

Desacatos, 43, 201–207.

Hernández y Hernández, F., AberasturiApraiz, E., Sancho Gil, J. M., & Correa Gorospe, J. M. (Eds.). (2020). ¿Cómo aprenden los docentes? Tránsitos entre cartografías, experiencias, corporeidades y afectos. Editorial Octaedro.

Humphreys, M. (2005). Getting personal: Reflexivity and autoethnographic vignettes. Qualitative Inquiry, 11(6), 840–860.

Iconoclastas. (2013). Manual de mapeo colectivo: Recursos cartográficos críticos para procesos territoriales de creación colaborativa. Tinta Limón.

Jiménez, A., & López, G. (2019). Retos de la educación superior latinoamericana para el siglo XXI. Un ejercicio pedagógico universitario en Colombia desde y para la nos–otredad en la perspectiva de la alteridad y la pedagogía crítica en tiempos del paradigma de la economía global. En Revista Atlante: Cuadernos de Educación y Desarrollo. https://www.eumed.net/ rev/atlante/2019/05/ educacionsuperiorlatinoamericana.html//hdl.handle.net/20.500.11763/ atlante1905educacionsuperiorlatinoamericana

Mannay, D. (2015). Visual, narrative and creative research methods. Application, reflection and ethics. Routledge.

RieraRetamero, M., HernándezHernández, F., de RibaMayoral, S., LozanoMulet, P., & EstalayoBielsa, P. (2021). Los métodos artísticos como desencadenantes de subjetividades en tránsito de la infancia migrante: un estudio en escuelas públicas de Barcelona. Antípoda. Revista de Antropología y Arqueología, 43, 167–192.

Rosa, G. (2012). Visual methodologies: An Introduction to researching with visual materials. SAGE Publications.

Tsalach, C. (2013). Between silence and speech: Autoethnography as an otherness-resisting practice. Qualitative Inquiry, 19(2), 71–80.

Authors:

Estibaliz AberasturiApraiz y José Miguel Correa Gorospe

Grupo de investigación Elkarrikeruz

Universidad del País Vasco/ Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea